Teaching Roundup: Georgetown, Fall 2019

As anyone who has suddenly started teaching three classes a semester will know, it is a big adjustment—a baptism of fire—but also an exciting time. Exciting, because it is a chance to experiment with new teaching methods and activities, a new syllabus, or a whole new course. Pedagogy is something that I also think is integral to being an excellent scholar—how many times have your students inspired a new approach to an old question? A new reading? It’s already happened to me—and has rightly become an increasing part of our scholarly community, especially in spaces such as this (a blog) and academic Twitter. So, with a view to sharing some of the success stories from the semester that you might want to adopt or adapt to your own courses, here is a rundown of what seems to have worked best– my top four:

Roman Persona —an identity-empathy challenge

Inspired by Amy Richlin’s (2013) article on role-playing in her Roman civilization classes, I adopted her template and made an individual “persona” for each student. Most of these descriptions were only a few lines long, but provided enough information for students to build on throughout the semester. Their persona came into play for a pre-circulated questionnaire they had to fill out for the Midterm exam, along with the construction of their own Roman name. In class, I often called upon students with specific identities to illustrate certain aspects of Roman society (such as having them sit in seats that reflect the stratified nature of seating in the Roman theater), or to role-play specific historical events from the perspective of their identity. In one part of the Final, they had to write about a major historical development (e.g. Caracalla’s citizenship edict in 212 CE) and how it would have impacted them, as well as composing an epitaph for their persona—thus bringing the class to an end! Since the personas were assigned at random in the first class–a great icebreaker is to have students read out their persona blurb to the class–they were often assigned a persona that resembled nothing like their own contemporary selves (especially in terms of gender, socio-economic status, etc.). My students reported that they really enjoyed this aspect of the class—they had never encountered anything like it before and it gave them something to invest in within the course that was individual to them; they had to truly think in another’s shoes (or sandals).

Digital Mapping of the Roman Empire

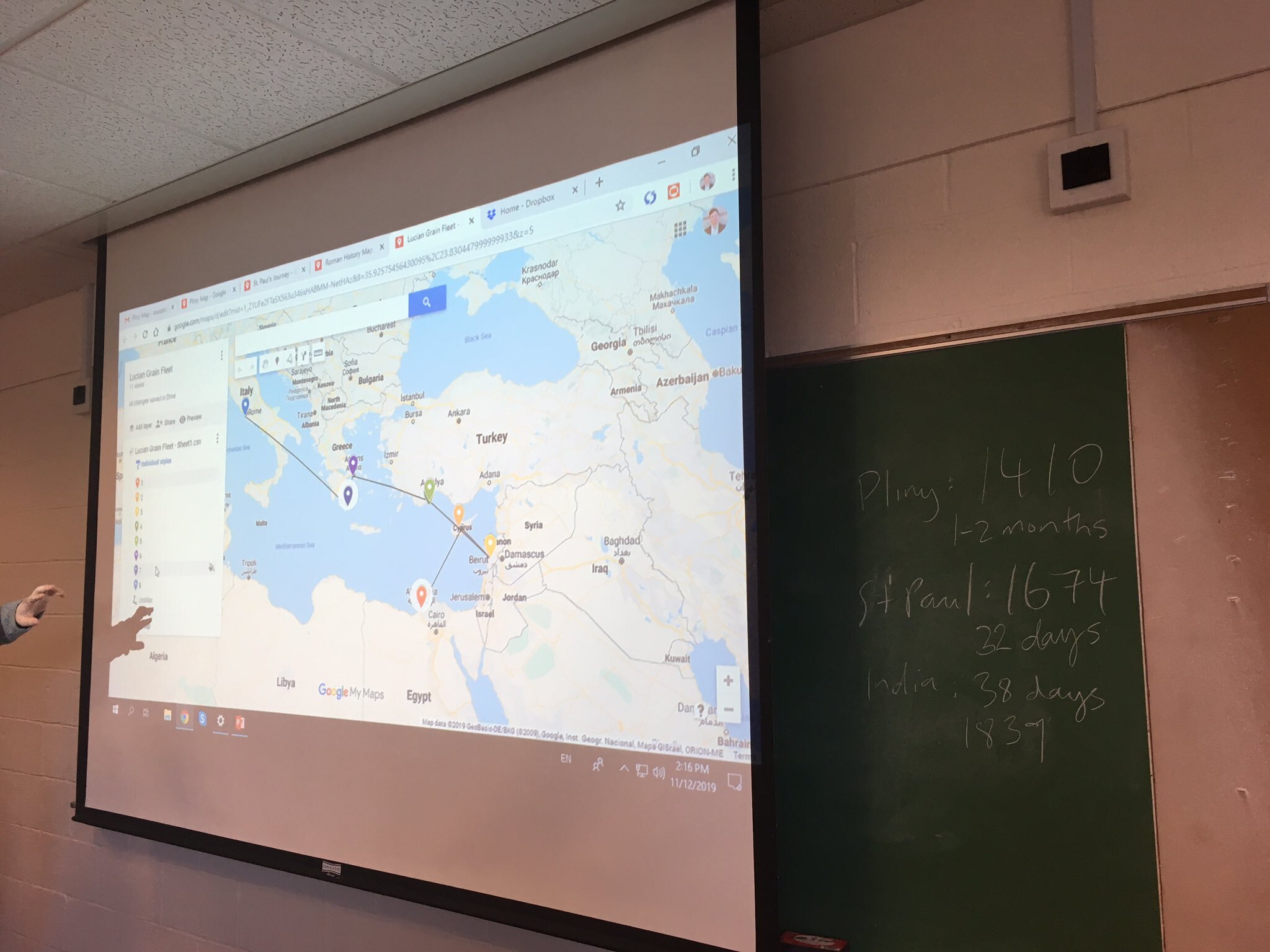

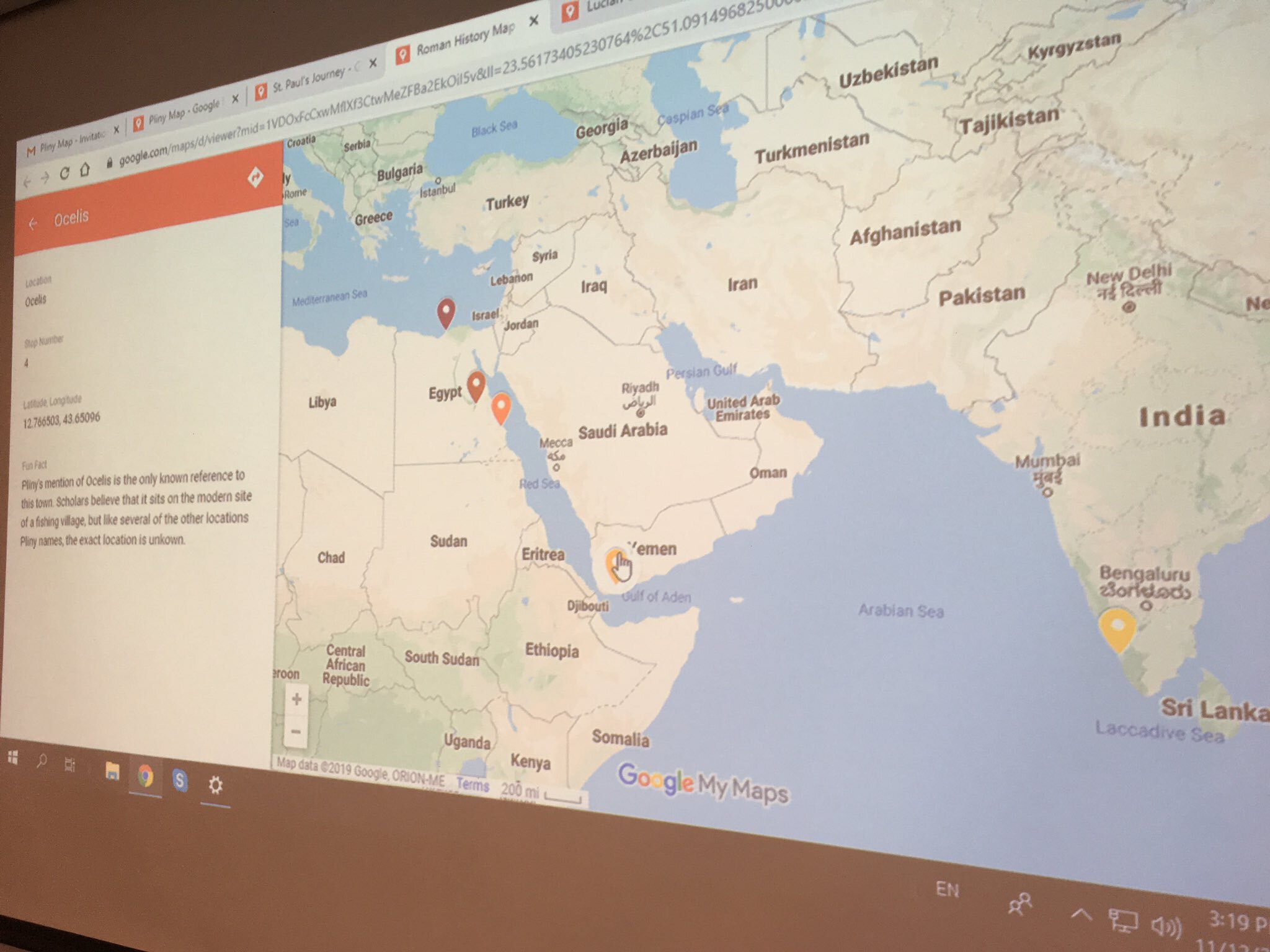

The map task is a mainstay of every Roman history exam. “Know your geography!”, we tell our students. To be sure, I did use one of these hard-copy map tasks in the Midterm, but then I came across Dr. Hannah Čulík-Baird’s (Boston University) Digital Tools page and saw how she had used a digital mapping task in her Cicero class. I decided to road-test this in a class day on Roman travel and trade, and assign the completion of the task for homework: they mapped trade and travel itineraries ranging from St. Paul’s journey to Rome to the pepper trade route from Alexandria to Muziris, India—also using the Stanford ORBIS project to calculate the cost of that travel, where possible. The students liked it so much and did such a great job that I integrated it into their take-home final exam, where they had to research some of the places from Hadrian’s travels around the empire and plot them on a Google Map, using coordinates and references gained from Pleiades and the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire, including information about what evidence we have for Hadrian’s presence in their chosen town or city.

You can see some of the results below!

One student’s digital map. Note that the connecting lines do not indicate the route of Hadrian’s itinerary. Students had to find two facts about each place they chose (they chose seven places) and find references in either ancient sources or modern scholarship to evidence these facts. None of these were absolutely perfect, but I was impressed by the research my students did and especially those that tried to find specific evidence for Hadrian’s presence at a place, e.g. the speech Hadrian have at Lambaesis.

Breaking out of the Essay Paradigm

We love our essays in Classics and Ancient History. They’re our bread and butter. But they also privilege certain students and, sometimes, stifle creative historical thought. Some of the best analyses of the Roman world that I saw this semester came out of unconventional media or genres of writing. For one week’s source analysis task, my students were asked to recreate 24 hours in the life of the prefect Flavius Cerialis and his wife Sulpicia Lepidina at Vindolanda on Hadrian’s wall, but to do so by writing in a dialogue form (between husband and wife at dinner) or as a letter (e.g. Lepidina to one of her friends), all the while referencing each part of the text with footnotes that anchored the text in the Vindolanda letters, which continue to be such a great digital resource, thanks to Oxford. In the Final, some students opted to write their Roman persona essay in the genre of a letter, for example a senator to his enslaved secretary, explaining the effect of the Augustan manumission laws. Freed of the boundaries imposed by the topic sentence and other (sometimes dull) hallmarks of the essay genre, my students engaged with the question in novel and much more meaningful ways.

In another class (Age of Augustus), I gave students the option of creating their final project in non-essay form. Only one decided to do this and he did so by creating a 3D model and tour of an Augustan colony in Minecraft, as well as writing a “manual” that explained his choices—as well as the limitations of using the program. He also walked me through the model in person (it is like a first person RPG computer game) and explained every single building, acknowledging issues, too (e.g. the need to allow for more room in plotting a grid plan, or allowing for a more expansive Forum). You can view a tour of his colony below—it’s pretty neat! I especially thought the sacrificial bull and altar were a nice touch! (All credit to my student Christopher Ziac for agreeing to share this here).

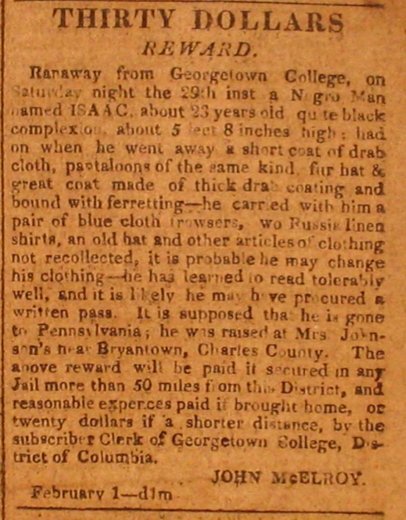

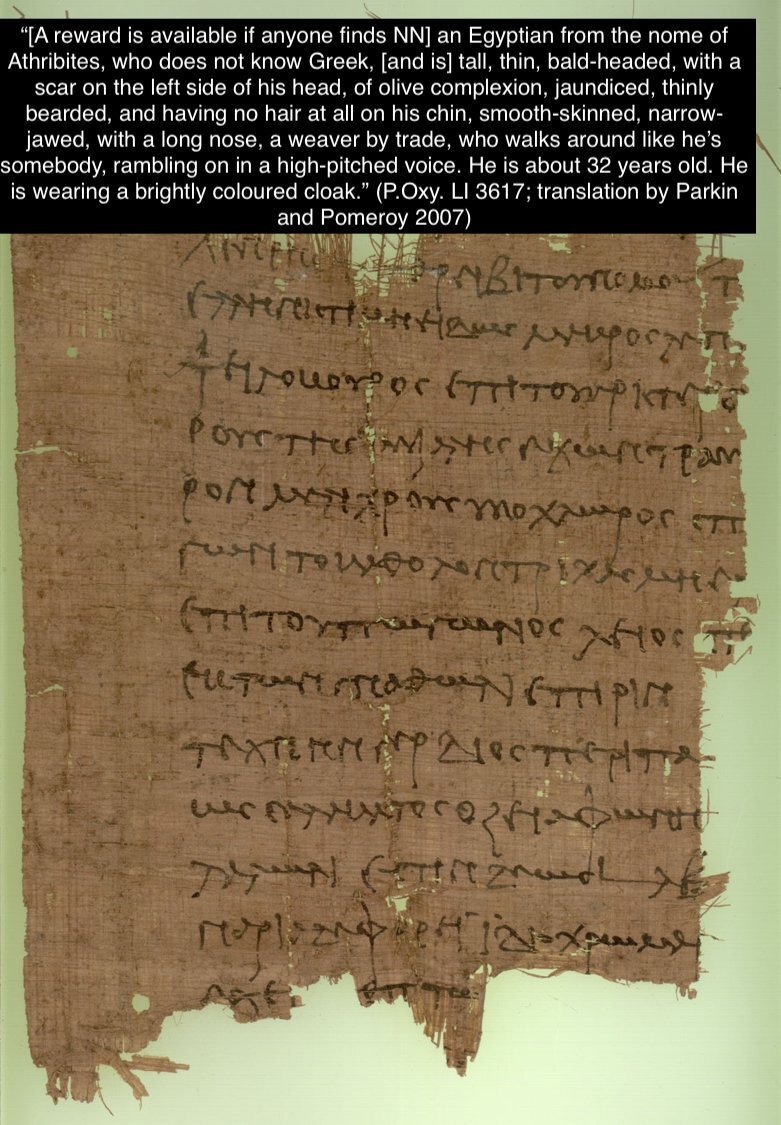

Connecting to the History of the Campus

For the class on slavery and emancipation in my Roman history survey, I decided to have my students compare select documents from the Georgetown Slavery Archive to documents they had already read for that class about Roman slavery and manumission. The exercise allowed them to think about the experience, institution, and legacy of slavery on their own campus in a new way, as they tried to connect or disconnect the experiences of Roman enslaved persons with those who had helped build and run Georgetown University. It was a sobering exercise and one that elicited much surprise from some students when they saw the similarities between the notices for runaway slaves side by side (see below).

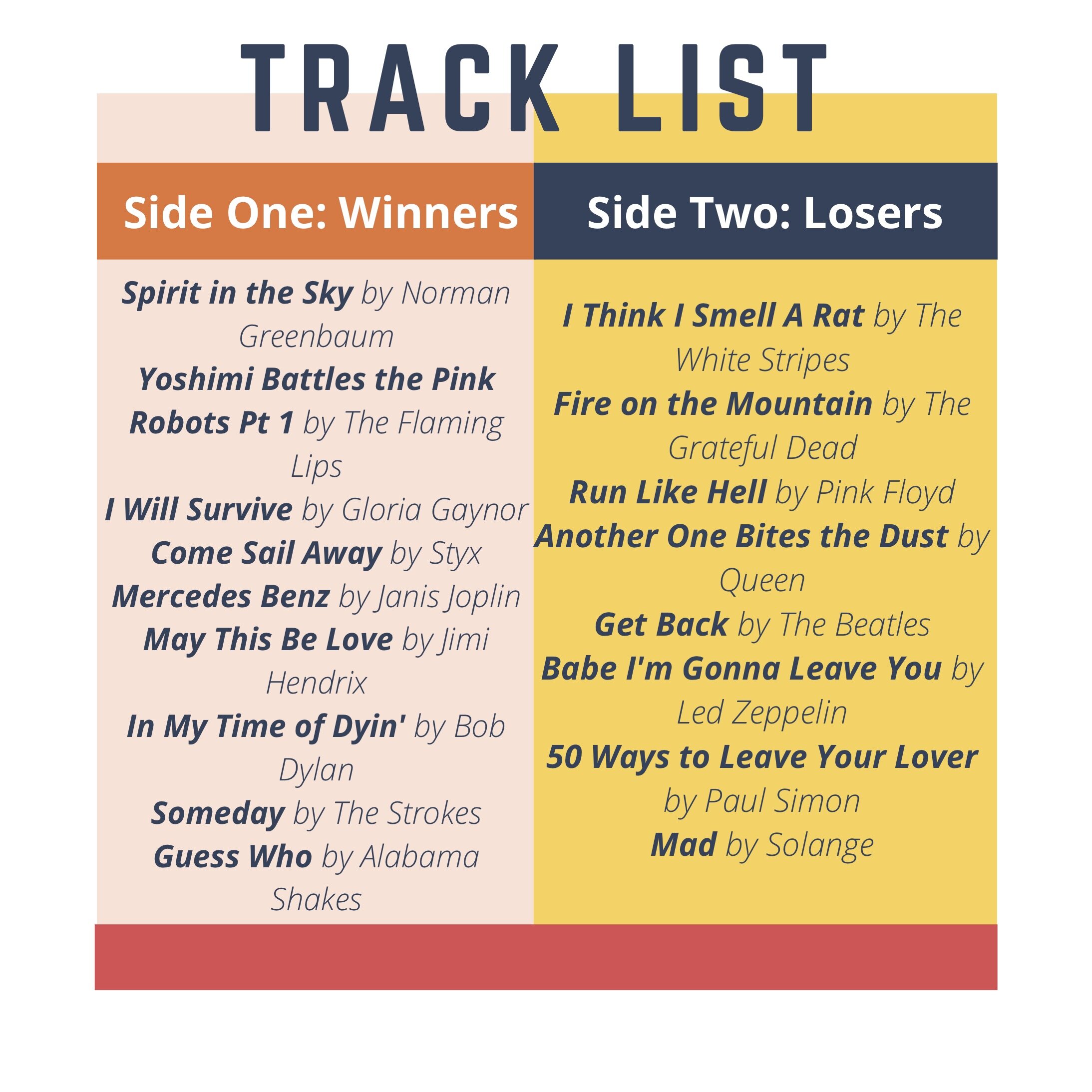

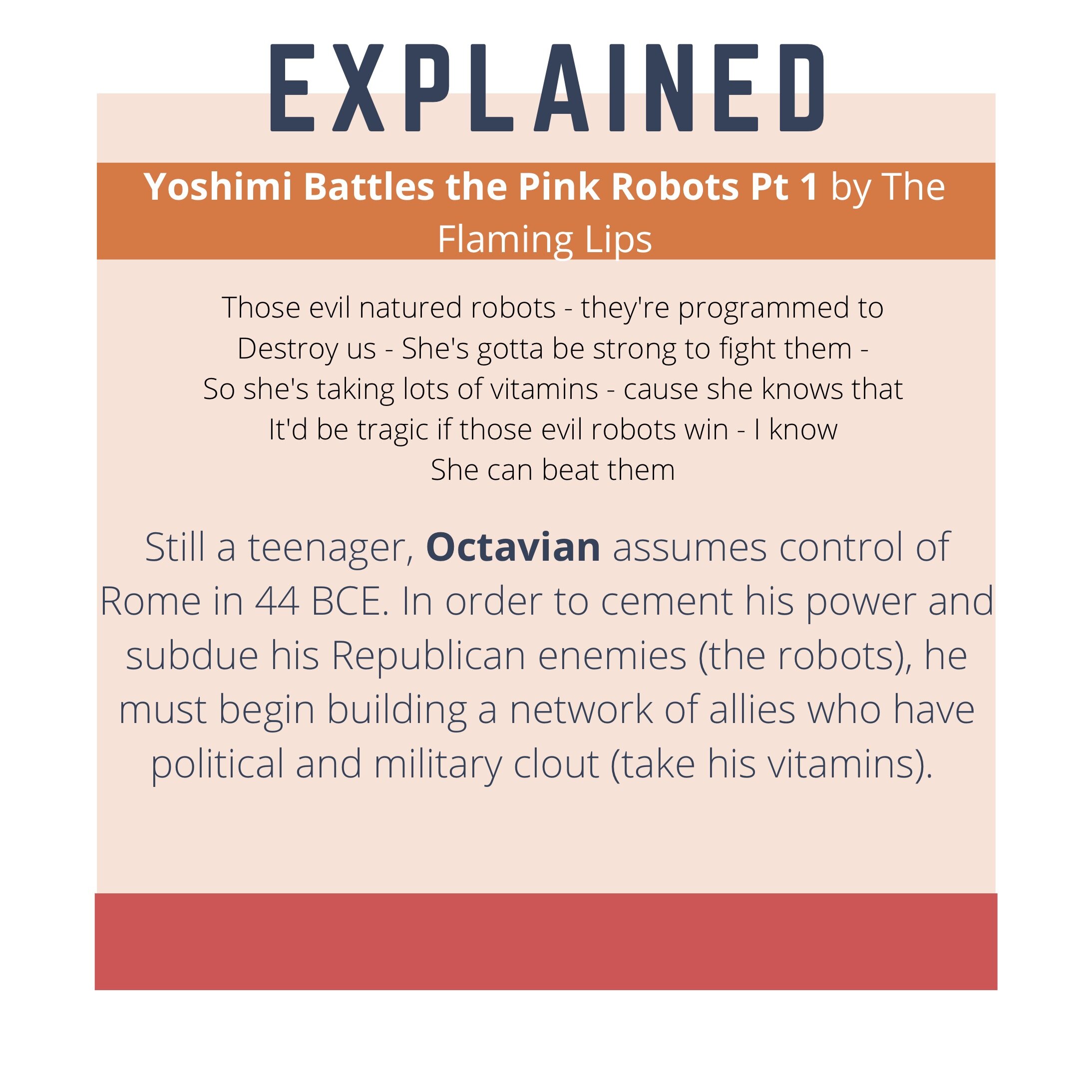

BONUS: An extra credit task that had me feeling a beat and a lyric

For my Age of Augustus class, my students also had the option of representing Octavian’s network, or key players in his circle, for the years 44-29 BCE for extra credit. One student, Ciara O’Neill (permission granted to post this here), took this to a creative height by putting together a mixtape with songs chosen—and lyrics singled out—for each person. Check out the Spotify playlist here and the playlist here with lyrics. In addition to finding very suitable songs, she has great taste in music and advised me that, in choosing the songs, she tried to find middle ground between our different generations. Thanks, Ciara!