[Review:] Pompeii in Color (ISAW-NYU)

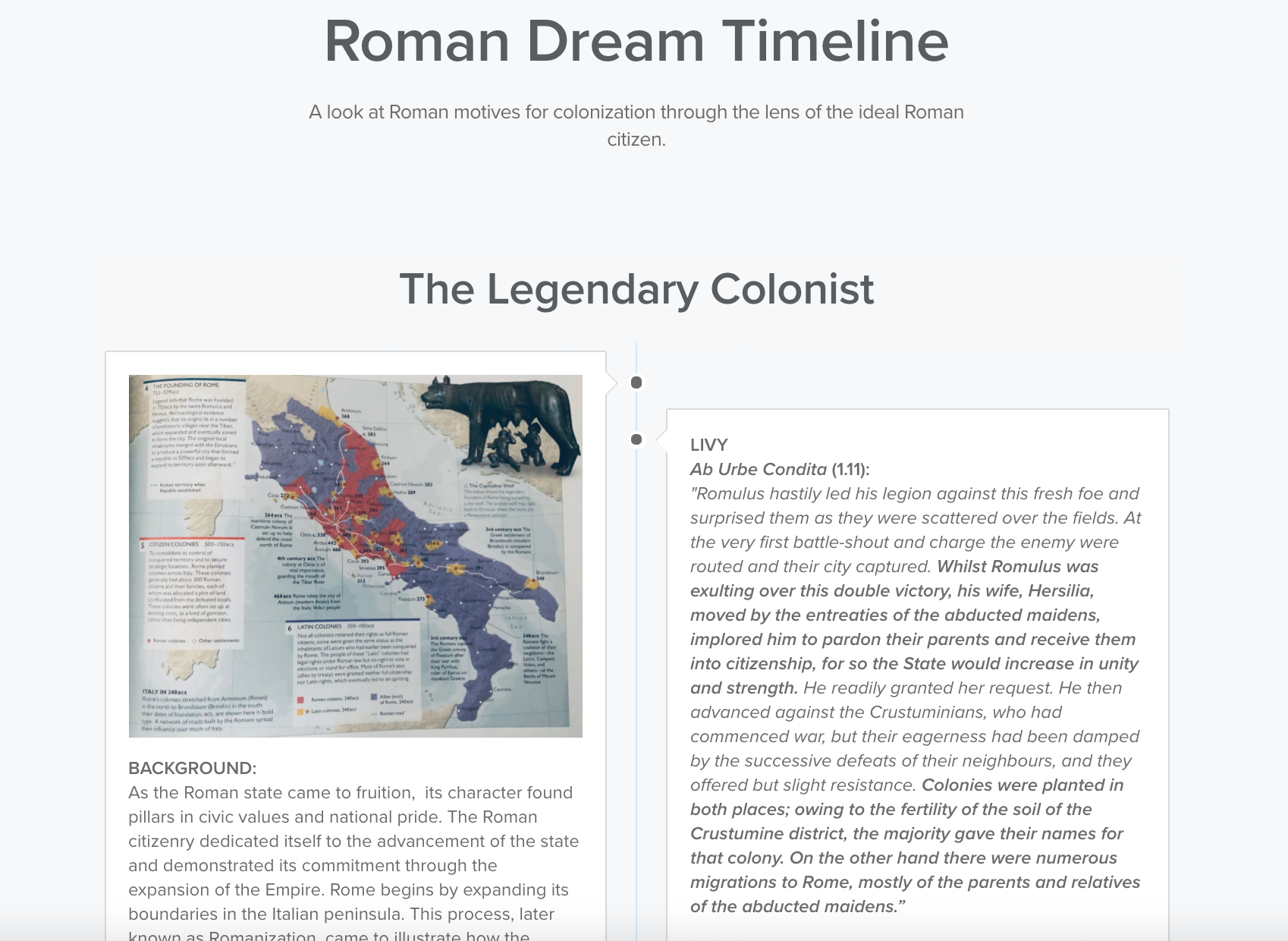

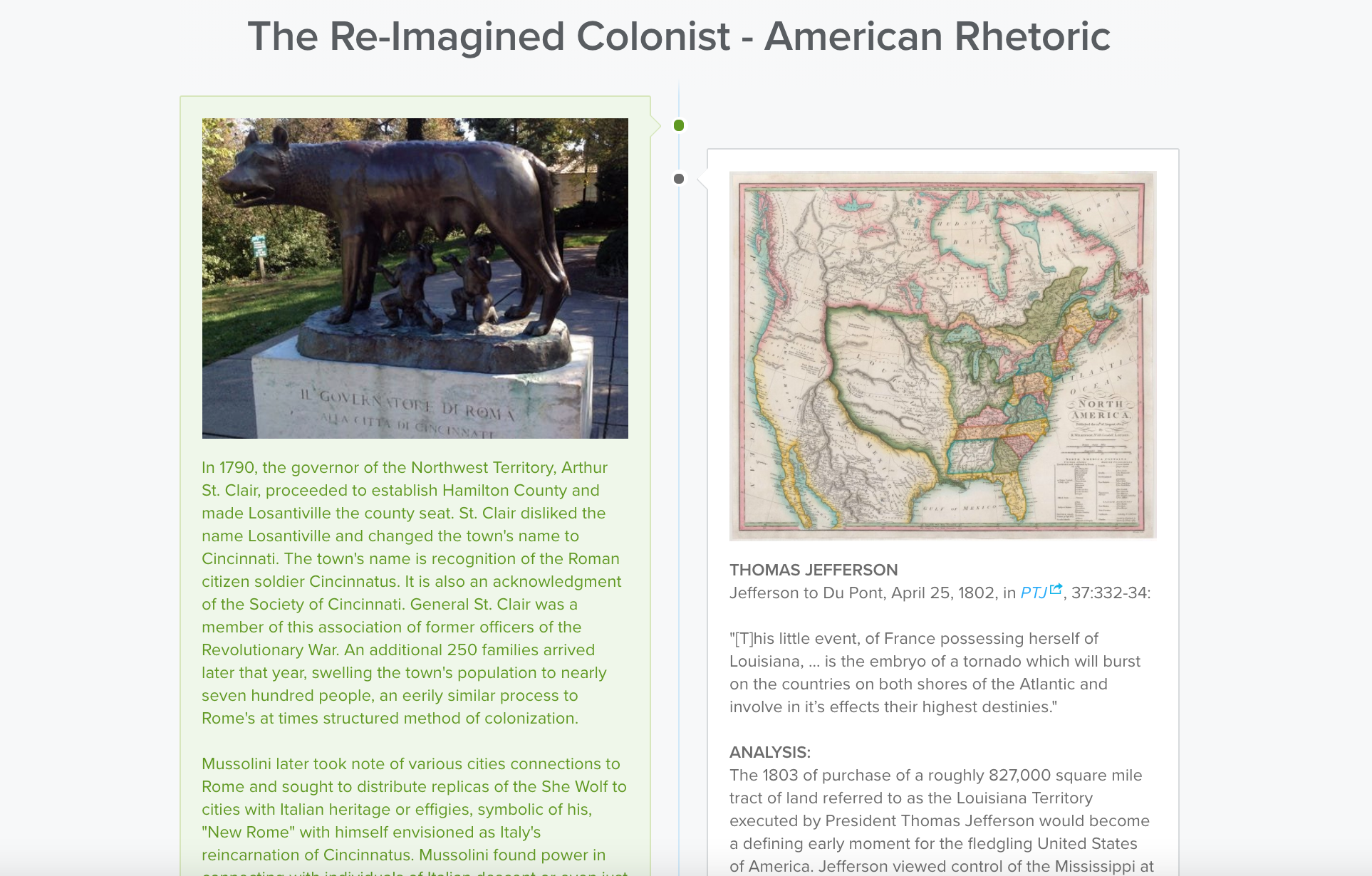

Comprising two small(ish) rooms, Pompeii in Color offers audiences in New York access to a remarkable number of frescoes from the many residences around the bay of Naples, rarely seen outside of the walls of the National Archaeological Museum in Naples (aka MANN). Accompanied by a slick website, which reiterates its major themes, and handy (but not entirely unheard of) digital walkthroughs of the Roman house on screens within the rooms, the exhibition is notable not only for the very fact that the curators have managed to bring such frescoes to the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW – part of NYU; on show, free to the public, until May 29, 2022)––a small coup in and of itself––but that they have drawn attention to a number of overlooked aspects in the lives of these frescoes.

To begin with, we are offered explanations and examples of the drafting process, the pigments and tools used, in the creation of these frescoes. At the other end of their life, we are also helpfully informed about the destructive treasure hunting (mostly under the Bourbon kings) that saw these frescoes cut from their walls, sometimes being reassembled into artificial compositions (e.g. still life groups). At the same time, the exhibit has assembled a number of frescoes on the same mythological theme, in this way establishing the existence of shared models, but also the differences between different artists and their execution of the same mythological scene, primarily represented by the story of Hercules and Omphale, as well as the discovery of Achilles at Scyros. All of this is very welcome.

But like its puzzling choice in title, Pompeii in Color does not exactly offer any one coherent message to its viewers—why wouldn’t we experience Pompeii in “color”!? That is partly what it is so famous for: the technicolor archaeological site! Faced with an eclectic embarrassment of riches, the curator(s) seem to have tried to make sense of a large, diverse range of frescoes under the umbrella of “color” and auxiliary, nebulous sub-themes, such as “the fantastic and the familiar”.

But how is “color” actually dealt with, beyond its technical application (yes, we are shown the actual pigments found in Pompeii), in the content of the frescoes themselves? Here, there were many missed opportunities and, I would hazard, some real tip-toeing around current scholarly moves to revise our understanding of polychromy, skin color in the ancient world and how racial difference was constructed in the colorful, diverse world of the Roman empire.

On the one hand, in numerous panels, we are told that skin tone denotes gendered differences—lighter skin for women, darker skin for men—which is not new nor controversial, that is, except when you are dealing with subject matter like Achilles on Scyros. In two frescoes (below) depicting the same scene of Achilles’ discovery, we cannot ignore the stark difference in the skin tone of Achilles versus the men around him, especially Odysseus—and yet this goes unremarked upon; neither the gendered elements (Achilles’ liminality on Scyros; his feminization and concealment as a “girl”) nor the Roman reception of them, such as Statius’ Achilleid, receive any attention here.

On the other hand, the curator(s) do recognize that skin tone could also denote race and ethnicity when dealing with the fresco from the House of Meleager depicting Dido abandoned by Aeneas. Acknowledging previous interpretations of the dark-skinned woman on the left as an allegorical representation of “Africa”, the curator(s) explain that:

“while variations in complexion can relate to gendered pictorial conventions, skin color can also denote race and ethnicity in ancient painting. Although the dark-skinned woman at left likely represents Carthage, scholars still speculate about her identity. Her presence reminds us today that the Roman world was diverse.”

Fresco from the House of Meleager, showing (left) a dark-skinned woman, sometimes identified as “Africa” or “Carthage”.

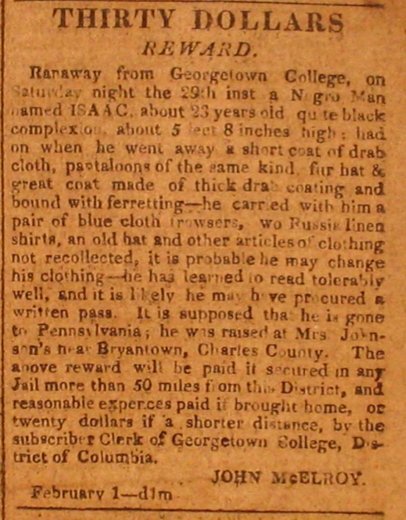

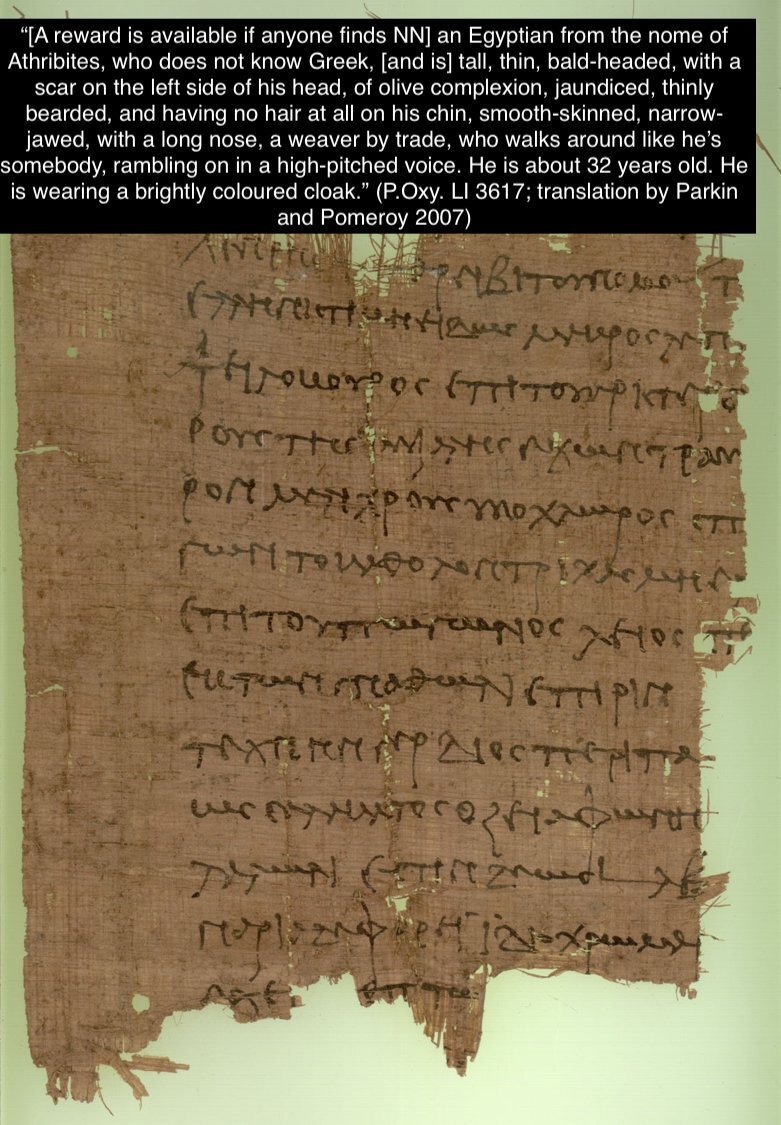

While this is a step in the right direction, for an exhibition about “color”, it is curiously non-committal (note the allusive “scholars still speculate”) in its assessment of skin color and what it could signify to viewers, not least because the field sits at a critical juncture in terms of reckoning with its own whiteness—a whiteness no less shared by the discipline of art history—and how we might tackle the question of race before race, as we know it, in its more recent and familiar instantiations (see, for example, the RaceB4Race conferences).

The exhibition’s weakness on this point is also on show when it explains the famous fresco from the House of the Triclinium (below), which depicts enslaved boys attending to guests at a banquet. The explanatory panel at first usefully dissects the scene, noting the formal hierarchy established by the difference in size between the enslaved attendants and free diners. And, yet, no attempt is made to explain the veiled light-skinned figure who extends an arm around a dark-skinned, dark-haired boy—even as they are noted as being in the scene. Are we not to think that this boy might be an enslaved puer, perhaps one of the deliciae, or “play things” that many a Pompeian household owned and who was often subjected to sexual abuse? Moreover, does the evidently darker skin of this boy denote his race, compared to the lighter skinned enslaved attendants at the bottom of the scene, as well as the veiled figure and other guests? All of these questions are, unfortunately, left unstated and unexplored.

“....does the evidently darker skin of this boy denote his race, compared to the lighter skinned enslaved attendants at the bottom of the scene, as well as the veiled figure and other guests? All of these questions are, unfortunately, left unstated and unexplored.”

Now, we might excuse this ambivalence, these silences, as simply the result of curatorial uncertainty—uncertainty about many things, but not least, how to situate such material within the present, shifting moment in the field. But to activate “race and ethnicity” in one fresco—and only the most obvious example of it—and not another, or to talk about gendered conventions only when it applies to heteronormative scenes and the gender binary of man/woman, but not in a very queer scene, speaks to me of the conservatism of this show.

This conservatism is felt in a number of other, quite startling ways. At one level, given the attention paid to the life of frescoes and the scratched-in words in the above banquet scene of the House of Triclinium (e.g. “BIBO”, “I Drink” is etched into the space above the figure holding the cup, to the right of the dark skinned boy—details helpfully provided in one explanatory panel), in another fresco, depicting the myth of Polyphemus and Galatea (immediately below: graffitied section is from the far right of the panel), no comment is offered as to why there are multiple graffiti etched, quite respectfully, into the red framing panel of the fresco (not transgressing onto the space of the scene itself). Given the burgeoning work on the relationship between art and text, frescoes and graffiti, this would have been a fascinating case study in the actual life of the frescoes and the material traces left behind from interactions with past viewers.

Finally, I was overjoyed to see the exhibition graced by the presence of the fresco of a female painter from the House of the Surgeon—an absolute rarity and one which deserves more attention (alongside the few accounts we have of women artists in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History 35.40). But the explanatory panel seemed not to care at all about the gendered implications of this fresco; there is no mention of the rarity of this scene nor whether women worked in this profession—instead, the curatorial label prefers to harp on the meta element of a painting going on within a painting. The label “Painter at work” says it all. A nearby, larger panel also mentions this fresco, but only offers up this opaque platitude:

“In one fresco we see an anonymous female painter dramatically framed by a window opening to the sky. Its message about the world-expanding potential of the arts would have been especially resonant in the fresco’s original, small interior room.”

Fresco from the House of the Surgeon, showing a woman painter at work, painting—labelled in the exhibition as “Painter at work”.

What is this “world-expanding potential”, you might ask? Well, it certainly doesn’t seem to be about the fact that a woman is here engaged in painting in her own right, nor that she might be one of the few women artists mentioned in Pliny’s account, nor that it might speak to a broader interest and practice of painting among women. No such possibilities are countenanced. This erasure by omission, for me, was just unacceptable. And more worryingly, the exceptionality of this fresco will remain unknown to the lay viewer who encounters this exhibition.

So, to keep it short: come for the frescoes—indeed marvel at them; but I wouldn’t necessarily stay to read and rely on the guidance provided by the curatorial panels. In the year 2022, I was astonished by some of the glaring omissions, the ambivalence on real questions of color vis-a-vis the history of colorism, and the general lack of a coherent message from the show. I’m sorry to say, but beyond the wow factor of a critical mass of frescoes in one space, and beyond some of the technical and thematic didacticism mentioned above, the opportunity to do more than merely expose the public to such an array of Roman wall painting has been squandered here.

“ This erasure by omission, for me, was just unacceptable. And more worryingly, the exceptionality of this fresco will remain unknown to the lay viewer who encounters this exhibition.

So, to keep it short: come for the frescoes—indeed marvel at them; but I wouldn’t necessarily stay to read and rely on the guidance provided by the curatorial panels.”

Note: all photos were taken by the author, with a phone. Photos were permitted at the time. If the curators wish for me to take down my photos, I will be very happy to do so.